It was 12th December, 1841. At an altitude of about 15,000 feet above sea level and temperatures dropping to minus 50 degrees, the air was thin enough to fog the brain, and the wind was sharp enough to cut through leather. In the searing cold, where the exposed skin succumbs to frostbite in mere minutes, while most of the world sought the warmth of fire, a shadow moved across the Trans-Himalayan desert. It wasn’t a nomad or a trader; it was the ‘Dogra Army’. At its head rode a man who transformed the treacherous snowy terrain into a strategic battlefield. This is the story of Zorawar Singh Kahluria – the general who fought where the gods were said to live! The man who defined the modern political boundaries of the Union Territories of Ladakh and Jammu & Kashmir.

Zorawar Singh Kahluria was born in 1784 into a Chandel Rajput family in the princely state of Kahlur (present-day Bilaspur), Himachal Pradesh. Very little is known about his early years, and much of it is rooted in folklore. It is said that he left his village when he was just 16 years old because of the family feud arising out of a land dispute with his uncles. The young Zorawar Singh Kahluria reached the Hindu pilgrim site of Haridwar in search of employment, where he met the jagirdar (feudal lord) of Doda (in Jammu & Kashmir), Rana Jaswant Singh. The Rana took Zorawar to Kishtwar and trained him to become a warrior. It was here, under the tutelage of the Rana, that Zorawar honed his skills in Archery and swordsmanship.

The political scenario of North India at this juncture was mercurial. By the 1800s, Maharaja Ranjit Singh had united the misls (principalities) of Punjab and had founded the powerful Sikh Empire. The army of Maharaja Ranjit Singh had vanquished the kingdom of Jammu in 1808, and the latter became a vassal state of the Sikh empire and was to be ruled by Mian Kishore Singh Jamwal, the Dogra ruler of Jammu. Gulab Singh Dogra, the son of Mian Kishore Singh Jamwal, was given the jagir of Reasi (in Jammu) by the Sikh ruler, and it was now that the fortunes of Zorwar Singh Kahluria would change. In 1817, he joined the service of Gulab Singh Dogra and immediately rose through the ranks as a soldier.

He ingratiated himself with the ruler by suggesting various methods to save money and to put an end to the pilferage happening in the warehouses. He suggested a profitable rationing system for food resources amongst the troops. Because of his administrative acumen, he was soon appointed the head of ration supply for all the forts north of Jammu.

After Maharaja Ranjit Singh wrested Kashmir from the Afghans in 1819, he placed it under the complete command of Gulab Singh Dogra’s family, and the latter was given full autonomy over his provinces and troops. Following this, Zorawar Singh Kahluria was appointed the wazir of Kishtwar in 1823 and was given the right to levy taxes and direct military action in the region as he saw fit.

It is pertinent to note that General Zorawar Singh Kahluria was known for his administrative integrity and his refusal to profit from his position. He never took a single penny from the state treasury for himself and sent the entire spoils of war directly to Raja Gulab Singh Dogra. His administration was defined by radical honesty, and he believed that every penny belonged to the people and the crown, not the commander. He was a man of Spartan discipline, and his legacy was built on his ambition to expand his kingdom.

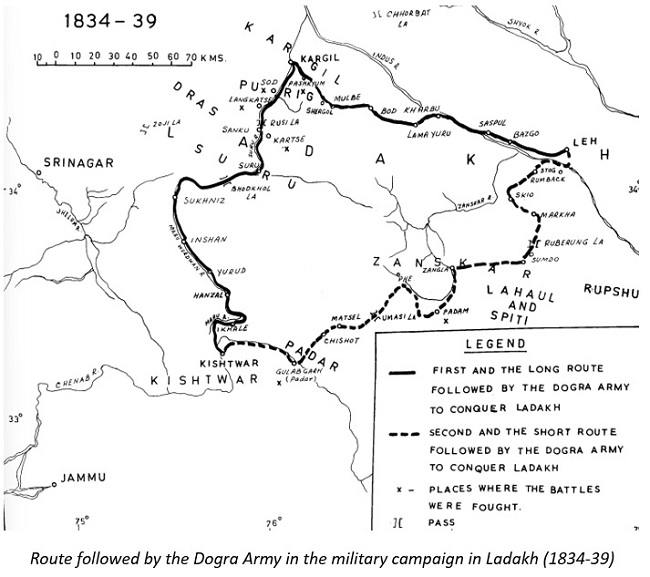

It was at this point that Zorawar Singh Kahluria started leading ambitious military campaigns. In 1834, he would lead his forces into the treacherous battlefield to conquer the kingdom of Ladakh, his biggest conquest and the one that sealed the fate of the kingdom and assimilated it into modern India. But why did the general conquer Ladakh? What were the circumstances that prevailed during the siege of Ladakh?

Ladakh had attained the monopoly in the Pashmina trade under the treaty of Tingmosgang in 1684, in conclusion to the Tibeto-Ladakhi-Mughal war. Under the treaty, it was decided that Tibetans would supply the Pashimna wool from western Tibet to Ladakh, which, under a separate treaty with the Mughals shall supply the same to Kashmir. This arrangement was followed throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Resentful of the monopoly which Ladakh enjoyed, Raja Gulab Singh Dogra started coveting the region for himself. Ladakh’s strategic location at the junction of the lucrative trade routes to Central Asia and Tibet made the conquering of Ladakh all the more appealing to the Raja.

The Raja’s general, Zorawar Singh Kahluria, a symbol of bravery and indomitable spirit, set out to conquer Ladakh. His military acumen, strategic approaches, and tactical planning secured a decisive victory for the Dogra army over the Ladakhi’s. The Dogra Army had been intensively trained by the general for high-altitude warfare in Kishtwar itself.

It is well known that, for Zorawar Singh Kahluria, the battlefield was the place where he belonged. The terrain was unforgiving, and perhaps the most formidable enemy the general had ever faced. It is imperative to put into context the many challenges his army had to face in conquering Ladakh.

Ladakh sits at an altitude ranging from 10,000 to over 18,000 feet. For an army coming from the lower hill areas, this was a physiological nightmare. At these heights, oxygen is significantly lower, leading to severe fatigue and reduced mental clarity. Due to narrow passes, the movement of the cavalry was nearly impossible. Zorawar’s men had to lead their horses through narrow, oxygen-depleted passes. These narrow passes forced his 5000-man army into single-file lines, making them extremely vulnerable to ambushes and stone-pelting from the heights. His strategy was to bypass the traditional routes (often blocked by enemies) and enter through impassable passes.

Because the land was barren, every grain of food and piece of firewood had to be hauled across hundreds of miles of mountains. To ensure food supply for his army, the general secured the food supply lines. He ensured that no crops were destroyed in the captured territories as his army was totally dependent on them. Forts were built, and the important ones were captured to establish his foothold and consolidate his power in the region. He strictly prohibited his army from looting the captured territories (as was the norm followed by the conqueror), which allowed him to gain the trust and respect of his new subjects. He negotiated with the local rulers and earned their loyalty.

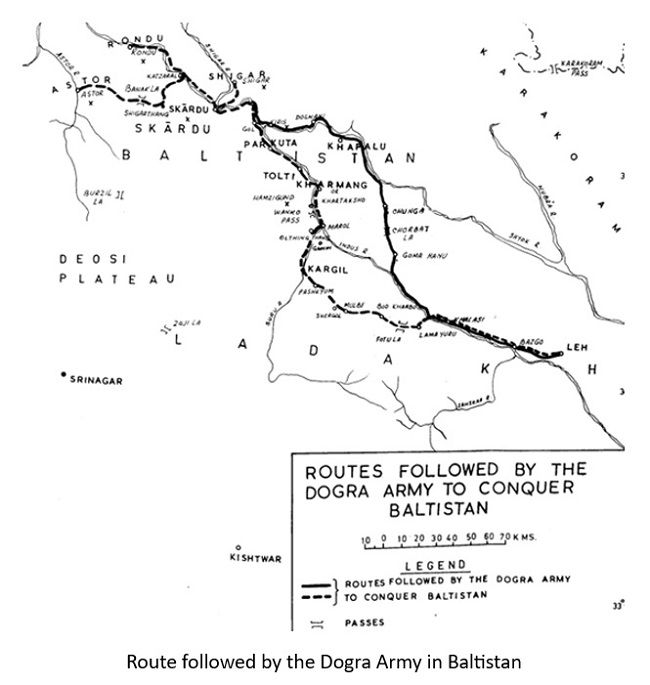

After establishing the Dogra rule in Ladakh and changing its course of history forever, the general set his eyes on Baltistan, which was an opportunity; created from the family intrigue among the Baltistan royals. Baltistan was another arid yet strategic zone with the Silk Road running through the Karakoram Mountains.

Capturing Baltistan involved crossing the fierce Indus and Zanskar rivers. The rivers were intense and dreadful. There were no bridges as they were destroyed by the Ladakhi defenders. The deep canyons of Zanskar made communication between different units of his army incredibly slow. Heavy logs of wood, approximately 40 feet in length, were hauled up to the river and used to cross it. Despite the daunting and innumerable challenges, the general and his army resolutely conquered Baltistan.

By the end of 1841, Gilgit-Baltistan and Ladakh came under the control of Gulab Singh Dogra. Having consolidated a hold over the northwest, Zorawar Singh Kahluria turned his attention to Tibet because of its economic importance (growing demand for Pashmina wool).

Zorawar Singh’s campaign against Tibet is written in the annals of history in bold letters. With an army of 6000 soldiers (including Dogras, Ladakhi, and Balti Soldiers), the general marched through the terrain no one had dared to cross. He managed to capture and consolidate the Tibetan territory upto Taklakot until the autumn of 1841. In his final campaign in Tibet, heavy snowfall blocked the passes, cutting off his supply lines. In his last battle at To-yo, the intense cold led to frostbites and his soldiers were incapacitated. They reportedly burnt the wooden stocks of their muskets just to get enough warmth to survive the night. In the concluding encounter, on December 12, 1841, General Zorawar Singh was hit in the shoulder, and a Tibetan lance went through his torso. Thus came to an end the life and story of a brave and ferocious warrior.

Such was his valor and courage that the Tibetans honored him by constructing a ‘Chorten Mani’ (A Tibetan Buddhist Stupa) also known as “Singh ba Chorten” near the village of To-yo, located in the Purang county of Tibet. This ‘Chorten’ is perhaps the greatest testament to Zorawar Singh Kahluria’s legend. It is said that the stones of his chorten hold the ‘mana’ or soul of the general within them. It is a rare moment in history where a conqueror was elevated to the status of a deity by the conquered.

General Zorawar Singh Kahluria displayed a legendary lack of fear towards the treacherous Himalayan terrain. His campaigns were not just battles against men, but a master class in overcoming the planet’s most inhospitable geography. He fought on the “Roof of the World”, reached the holy lake Mansarovar, and was truly the lion of the mountains. We must never forget that India’s northern frontiers weren’t drawn by diplomats in air-conditioned rooms but were carved by the tip of a Dogra sword!

In the end, it was not the steel of an enemy that felled the Lion of the mountains, but the merciless breath of the mountains he had spent a lifetime taming!

No responses yet