Over the last decade or so, modern pan-Indian and global scholarly discussions have shifted towards the great dynasties of ancient and medieval India, which ruled for centuries, not only in the Indian subcontinent but also in parts of Southeast Asia. The maritime prowess of these dynasties enabled them to establish exceptional trade ties with Southeast and South Asia. This economic contact resulted in the dissemination of culture, religion and heritage to the land beyond the shores!

One such dynasty, or rather an empire whose naval might has been historically glorified, is ‘The Cholas’. Their military expeditions (mainly of Rajendra Chola I against the Srivijaya Empire of South Asia in the 11th century) have been well documented, and they are a testimony to the supreme maritime force that was the Cholas. In contrast, there was one such kingdom whose maritime legacy has often been overlooked. We often hear about it in the context of Ashoka, the warrior prince who conquered it with brutal might and later expressed repentance for his actions (well, that’s a different story altogether!). This kingdom is none other than ‘The Kalinga’.

Kalinga’s maritime history is deeply rooted in the cultural Indianization of South-east and South Asia. It was largely driven and facilitated by the merchants and the monks who conquered with commerce and culture, – a process that was organic and was devoid of spectacular military campaigns and therefore, failed to capture the historical imagination as powerfully as that of the Cholas. It is solely for this reason that Kalinga’s significant contribution to the Indianization of the Southeast and South Asia in the early decades of the Christian era has been historically neglected.

Kalinga, historically referred to as the eastern coastal region between the Ganges and the Godavari rivers, encompasses all of modern-day Orissa and parts of Andhra Pradesh. Kalinga’s strategic location was its biggest asset. The naturally laid out inland riverine connectivity (The Ganges, Mahanadi, Baitarani and Brahamani) promoted the transportation of resources from the deeper jungles of Kalinga to the far flung areas. Its vast and dense jungles were a source of essential raw materials especially hardwood (Teak, Sal and Piasal) which formed the basis of the shipbuilding industry. The famous Black tuskers of Kalinga were the most sought-after mammoths who were sold even to the Mauryan Empire to be deployed in the battlefield. Kalinga was rich in precious stones, especially diamonds, and other forest produce (sandalwood, cinnamon, iron ore, ivory etc). This region remains rich even today, though the nature of its wealth has shifted from maritime trade to industrial and mineral dominance.

On the face of it, it does appear that Kalinga was self-sufficient in every aspect of life, but then what prompted the Kalingans to look to the East? Why did they establish the cultural and trade ties with Southeast and South Asia? Was it a political necessity? Was it the aftermath of a war? Was it for religious purposes? Who were the ones who initiated this contact? Was the Indianisation of South-east and South Asia a sort of colonialism?

There are multiple theories propounded for explaining the venture of the Kalingans into the Southeast and South Asia. One such theory attributes the said migration of Kalingans to the invasion by the foreign forces such as the Greeks, Sakas and the Kushanas in the early centuries of the Christian era. However, this seems a little unacceptable as the foreign invasions in the early centuries were primarily focused on areas of the Gangetic plain and not beyond that. The migration of Kalingans is also attributed to the conquest of Kalinga by Ashoka in the 3rd century BC. However, there is no historical or archaeological evidence for the same. But it does appear rather indirectly in one of the rock edicts of Ashoka that, after the Kalinga war, the remorseful emperor talked not only of the ‘dead and deported’ but also of the ‘fortunate who have escaped’ without mentioning the land to which they escaped.

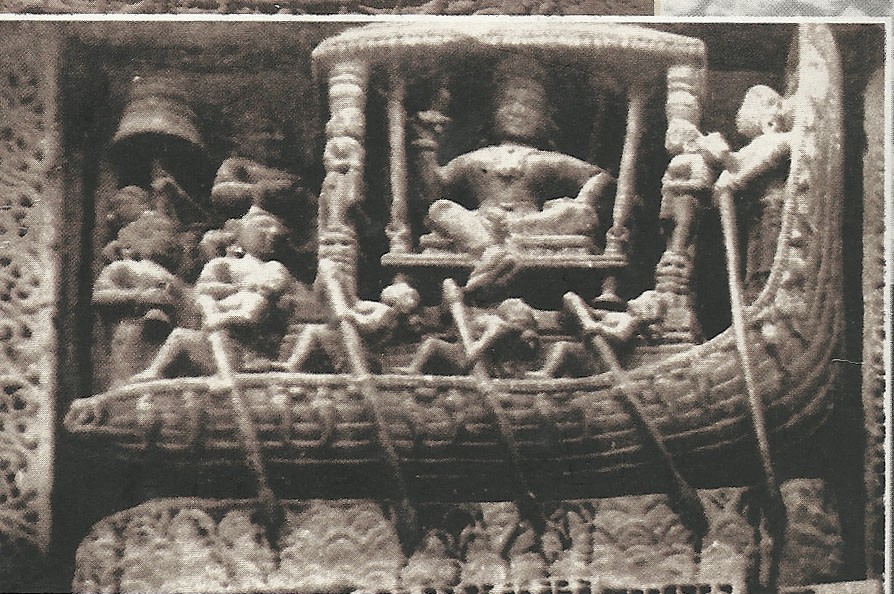

The mass exodus of Kalingans to Southeast and South Asia was not driven by a single event, but by a combination of economic necessity and religious zeal. Kalinga’s expansion was largely ‘Pacific Penetration’, a slow cultural osmosis led by traders. The skilled seafarers of Kalinga, known as ‘Sadhabas’ or the ‘Masters of Mahadodhi’ (ancient name for Bay of Bengal), possessed expertise in sailing and demonstrated an extensive knowledge in both open sea and coastal navigation. They had a deep understanding of the winds and worshipped their ships with great reverence. They were not a specific caste but a wealthy social class of explorers, merchants and seafarers. They were instrumental in carrying out trade with Southeast and South Asia and acted as cultural ambassadors. To commemorate them, ‘Bali Yatra’, a trade fair is organized annually even to this day, depicting the historical recollections of the cultural and trade framework.

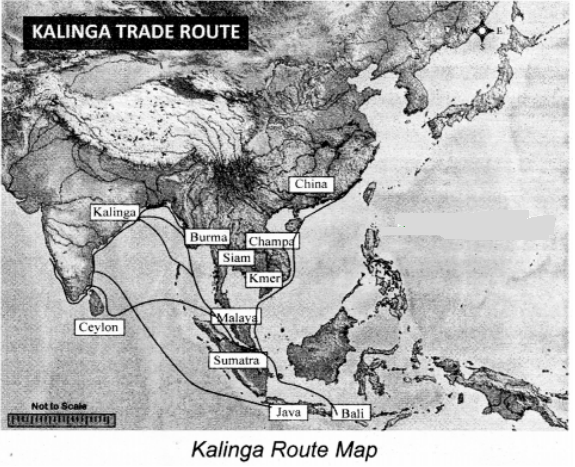

The commercial endeavors were undertaken to forge amicable trade relations with far-flung regions of Java, Sumatra, Bali, Borneo and Sinhalese in Southeast and South Asia. This not only brought material prosperity to Kalinga but also disseminated its culture and religion in foreign soils which culminated in the establishment of a series of kingdoms, each mirroring one of the original Indian states.

The kingdoms of Cambodia, Champa, Sumatra, Java, Bali, Burma, Thailand and other minor states of the Malay Peninsula show distinct traits and cultural and historical remnants which are a result of centuries of interaction with and influence of Indian culture. The Indian culture had a tremendous influence on the people who lived there. The cultures, traditions and rituals of these modern-day states have preserved a familial resemblance that may be linked to the fact that they all originated from the same place. There is plenty of historical evidence of the same, chronicled by the Chinese and Buddhist explorers and historians.

The Buddhist chronicles of Ceylon illustrate the story of Prince Vijaya, the son of the king of Simhapura, a well-known city in Kalinga. He set off on a journey to Ceylon along with his followers and later took the throne for himself and became the first monarch of the island. Sanghamitra, daughter of Ashoka, set sail from Tamralipti to Ceylon to spread Buddhism. She was also accompanied by eight Buddhist families from Kalinga, who introduced the Theravada school of Buddhism to the uninhabited island and settled there permanently. A stone inscription in Sri Lanka recounts the founding of the Sinhalese dynasty by one of the kings of Kalinga. The coastal region of Burma was populated by the early Kalinga traders and merchants who eventually settled there and called themselves ‘Tolaing’, as they hailed from Trikalinga.

Suvarnadvipa, the archipelago that consisted of Bali, Java, Sumatra, Borneo and Malaysia, was populated by the inhabitants of Kalinga. Legends state that Java was ruled by three successive generations of the Kalinga ethnic group. According to contemporary Chinese and Arab historians, the formidable Sailendra dynasty of Suvarnadvipa can be traced back to the ‘Sailodbhaba’ dynasty, which ruled much of Odisha during the 7th century AD.

The famous legend of a Brahmin named Kaundinya, who sailed from Kalinga to the Mekong delta forms the historical foundation of the Cambodian state. After defeating the local Naga Princess Soma in battle, Kaundinya eventually won her hand in marriage and united her people. This legendary union introduced Indian culture, religion and traditions to the region.

The Indianization of Southeast and South Asia was never a story of conquest but rather a profound cultural synthesis. Kalinga acted as a bridge, transforming the Bay of Bengal into a ‘cultural lake’ where trade and faith flowed freely. The most poignant ending to this story is carved in stone. The temples of Borobudur and Angkor Wat, built on the lines of Indian Architecture, are not just Indian temples but a physical manifestation of a successful cultural union. The fact that when one visits a temple in Bali or a ruin in Cambodia, one can truly feel the unmistakable heartbeat of ancient India, is cathartic.

The Indianization of Southeast Asia via Kalinga represents one of history’s rarest phenomena: colonization by trade and culture. It took the seeds of Indian culture and grew its own garden, resulting in a civilization that was grander and more glorious.

No responses yet